Beethoven 3 5 7 1958 Solti Vienna Review

The 'tremendous' Third Symphony is both great music and a forcefulness beyond music. How, asks Richard Osborne, accept conductors met this challenge during the work's 90-year-long recorded history?

Welcome to Gramophone ...

We have been writing near classical music for our dedicated and knowledgeable readers since 1923 and we would love you to bring together them.

Subscribing to Gramophone is piece of cake, you can choose how you want to bask each new effect (our beautifully produced printed magazine or the digital edition, or both) and also whether you would like access to our consummate digital archive (stretching back to our very first issue in Apr 1923) and unparalleled Reviews Database, roofing 50,000 albums and written past leading experts in their field.

To find the perfect subscription for you, simply visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe

Writing in his diary in Houston on Feb 10, 1966, Sir John Barbirolli pondered, 'Foreign how the Eroica exhausts me these days. It may well be considering I am actually beginning to plumb its depths. It really is a tremendous piece, isn't information technology?'

'Tremendous' is the right word for theEroica, whether it's used as a term of general approbation or as a description of a symphony before which musicians and audiences do, indeed, take cause to tremble.

In 1967 the BBC Symphony Orchestra invited Barbirolli to tape theEroica. Broad in tempo and richly sung, it is a reading that's fathoms deep. Off-trend at the time, it obviously awed the BBC players, much as information technology had awed the Berlin Combo earlier that same year. And herein lies a dilemma. When the Berliners played theEroica under Karajan in London in 1958, Neville Cardus noted that the work was presented 'as a strongly shaped example of musical art, not entirely every bit a force beyond music'. The fact is, this timeless manifestation of the imperturbability of the human spirit is both: an incomparably crafted artwork and a force beyond fine art.

TheEroica'southward defining document, written during the time of its composition in 1802-3, is the Heiligenstadt Testament in which the 31-twelvemonth-onetime Beethoven reveals how encroaching deafness has brought him shut to suicide merely how, counselled by his art, he has resolved on patience. 'I hope my decision will remain firm to endure until it pleases the inexorable Parcae [Fates] to break the thread.'

TheEroica is a mountain of a symphony. The ascent is steep and problematic, with a summit (the terrifying macerated seventh at bar 166 of theMarcia funebre) that is reached later a fugal expedition through a landscape which becomes e'er more forbidding. The descent is a joy, nonetheless we remain on the same mountain, and similar all descents information technology also has it perils.

For that terminal movement Beethoven takes the world-defying, life-affirming Prometheus as his guide. It's a movement, unique for its time, which is tied thematically to things that have gone before. When the fugal variations finish and a solo oboe sounds the starting time of thePoco andante, Beethoven is recasting at a college pitch and in a major key i of theMarcia funebre's darkest memories. Donald Tovey likened the moment to the opening of the gates of Paradise; and Wilhelm Furtwängler must have thought likewise, since he greatly extended the pause (edited out in his studio recordings by literal-minded technicians) before the oboe's entry.

TheEroica is unique in some other sense. Information technology is the showtime symphony in history to invite what we now call 'interpretation' (every bit early every bit 1807, audiences were offered printed explanations), though estimation was hardly a gene in its earliest days. Equally with many 'menstruation' performances of the 1980s, simply playing the notes was a sufficient claiming. Information technology was not until Wagner'south arrival on the scene in the 1840s that forensic test of the music'due south inner content began in earnest.

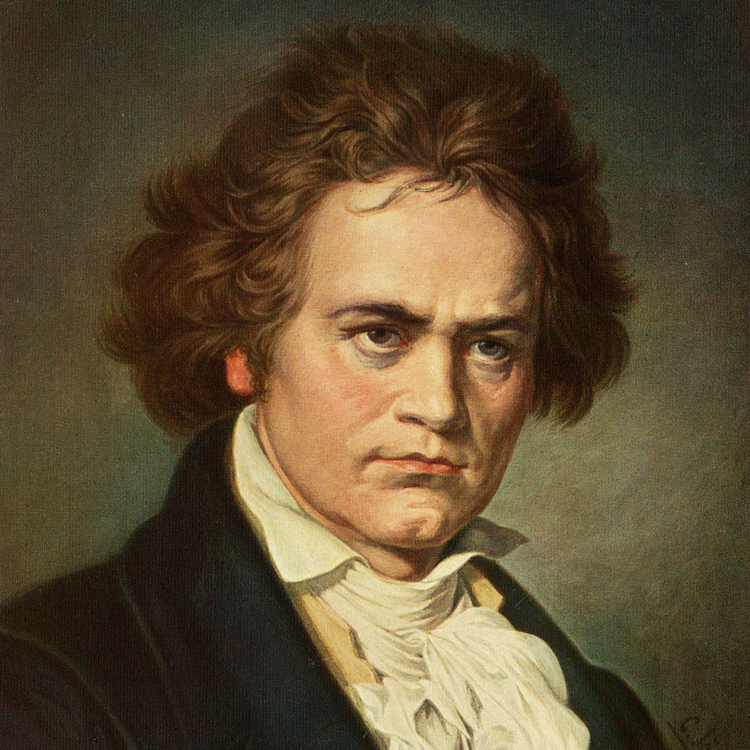

FURTWÄNGLER AND TOSCANINI

Furtwängler and Toscanini, ii of theEroica'southward almost powerful interpreters, were heirs to that forensic thinking. Information technology also happens that their own almost musically devastating performances date from the years before and during the 2nd World War, when Europe was once more blighted by conflict and the posturings of charismatic leaders, much as it had been at the time of the symphony's cosmos.

That said, Arturo Toscanini always presented himself equally a literalist. 'Is-a not Napoleon! Is-a not 'Itler! Is-a not Mussolini! Is-aAllegro con panache!' he screamed at the BBC So during a rehearsal in 1937. A volcanic live performance with the NBC Symphony Orchestra dates from the post-obit twelvemonth, though it's the live 1939 Victor recording which is to be preferred now that the sound has been tidied up. Information technology marries high-tension drama with beautifully proportioned lines and aMarcia funebre that moves like a progress of the Stations of the Cantankerous. It's a very Italianate reading, the mood of the Verdi Requiem not far distant. Yet nothing can detract from its humanity or searing impact. If there is a downside, it'south that there are places in the finale where the playing seems rushed. In that location is a similarly vivid 1953 functioning but the rhythms are a touch more sclerotic and one misses the oboe-playing of Robert Bloom which is so sublime a characteristic of the two pre-state of war performances.

Toscanini was peerless in the Seventh Symphony, where rhythm is the wellspring. In the Eroica – a vast symphonic drama where rhythm is linked to a new class of differential gearing which drives and co-ordinates Beethoven'southward boggling aggregation of images and ideas – Wilhelm Furtwängler was the greater primary. No conductor on record is more meticulous in his observation and realisation of Beethoven's lavish array of dynamic markings. Given the depth of sound theEroica demands if its impact is to be fully felt, this is an amazing feat, both by him and the Vienna and Berlin orchestras with which he principally worked.

Since the release of the technically excellent post-war RIAS recordings, information technology'south arguable that Furtwängler's live 1950 Berlin performance is the one to have, though in the high peaks of theMarcia funebre and in the finale, the 1944 Vienna performance remains unsurpassed. An early LP of the 1944 version transferred the single-microphone, reel-to-reel Magnetophon recording a semitone precipitous, making the performance seem brighter (and faster) than it was. But it comes upward very well in the newest CD transfer.

None of Furtwängler'southward contemporaries in pre- and postal service-war Berlin came close to matching him in theEroica, though Paul van Kempen'due south 1951 Philips recording with Furtwängler'southward own Berlin Combo was rightly held in high regard.

THE Early YEARS

The effective history of theEroica on record began with the arrival within a yr of one some other of electrical recording and the 1927 Beethoven centenary. Henry Forest, who had already fabricated a heavily cut acoustic recording, and Albert Coates were the first out of the blocks: an apt phrase given the frenetic pace at which both conductors have the kickoff movement. The Coates is not only fast but impossibly wayward. Wood has the better orchestra and an birthday surer structural grasp. His account of theMarcia funebre has pathos without sentimentality, a very English solution at the time. Wood's younger contemporary Sir Thomas Beecham didn't record theEroica (one of the few Beethoven pieces he genuinely admired) until 1951-52 (for Columbia). Distinguished by fine air current-playing, it is a performance of intelligence and sensibility, characteristically alarm.

Betwixt 1927 and 1936 recordings by Max von Schillings, Hans Pfitzner, Willem Mengelberg and Serge Koussevitzky allowable the catalogue. Mengelberg draws glorious playing from the New York Philharmonic, just swooning string portamentos in theMarcia funebre are an offence in any age. Koussevitzky's 1934 London Philharmonic Orchestra set was admired in its day, but his grasp of the symphony'southward architecture would exist firmer, and the playing no less vivid, when he re-recorded information technology with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1945 (RCA, 5/70 – also nla). In the cease it was Felix Weingartner'due south 1936 recording with the Vienna Philharmonic which cornered the pre-war marketplace. 'Adept lean beef' was the phrase coined by Peter Stadlen to describe Weingartner'south Beethoven. Only a somewhat matter-of-fact feel to the playing of theMarcia funebre and an indeterminate touch with the finale rob the performance of an bodacious place in the pantheon.

LP AND THE ARRIVAL OF STEREO

A practicedEroica, Deryck Cooke noted in these columns, needs 'not only a fantabulous line but a tense rhythmic impulse; non only a vicious strength only a sense of mystery'. He was writing (with approval of everything except the recorded sound) about the 2nd of Jascha Horenstein'due south ii LP recordings. In that location were a number of such recordings in the early on days of LP, none more distinguished than Erich Kleiber'due south with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra. Classically conceived, with a fine residue between the symphony's dramatic and expressive elements, it has many of the same qualities equally Toscanini's post-war accounts, without the sense of the car beingness in permanent overdrive. Some thought George Szell a car. 'Yes, but a very good one,' retorted Otto Klemperer. Szell'southward 1957 ClevelandEroica proves Klemperer's signal. Here is discipline without regimentation, and an attention to detail, meticulously registered by the orchestra, that is little short of breathtaking.

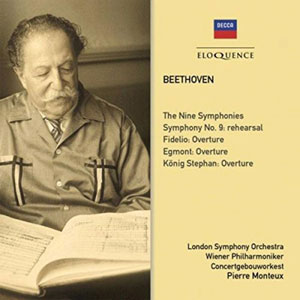

The arrival of stereophonic sound in 1957 was a red-letter day for theEroica, both for the spatial dimensions it provided and for the revelations its brought in the finale, where Beethoven lavishes enormous care on the part-writing for the strings. Two great interpreters who survived into the stereo age and who continued to seat their violins antiphonally were Klemperer and Pierre Monteux.

It was a happy chance which led Decca, pioneer of country-of-the-fine art stereo sound, to invite the 82-twelvemonth-old Monteux to record theEroica in December 1957. It was his first recording for the company, and his starting time with the Vienna Philharmonic, that most musically experienced – one might say 'historically informed' – ofEroica orchestras. With Monteux as a wise and galvanising presence, the orchestra is at the peak of its powers, bringing a variety of weights and colours to a reading that is as remarkable for its structural accomplish every bit it is for its textural clarity and the keenness of its rhythmic articulation. 'In theEroica there is no status quo,' noted Leonard Bernstein, whose 1964 New York Combo performance is a wonderfully vibrant affair. Few conductors are more keenly aware of this than Monteux, whose long clan with that other epoch-changing piece, Stravinsky'sThe Rite of Spring, conspicuously stood him in practiced stead where theEroica is concerned.

One thing that may take surprised the Vienna Combo was Monteux's textual purism: no extra winds and no extension to the trumpet line in the beginning-motion coda – this around forty years before the publication of the modern Urtext, Jonathan Del Mar's Bärenreiter edition. (Cited simply woefully misrepresented by David Zinman in a 1998 Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra recording in which some of Beethoven's most starkly fatigued oboe lines are coyly embellished.)

Of Otto Klemperer'south 2 EMI studio recordings, it is his 1959 Abbey Route version which must have precedence, largely because of the space and caste of interior detailing stereo allows. Klemperer'southward is a Stoic'south view of the work, one that pays homage to those 'inexorable Fates' to which Beethoven makes reference in the Heiligenstadt Testament. Yet Klemperer was too a great theatre usher – hisFidelio was more or less without compare in its day – which gives the performance its own ineluctable life.

The 81-year-one-time Bruno Walter was no longer a divider of the violins when he fabricated his 1958 Columbia Symphony Orchestra recording. It is a noble performance, rather more 'together' conceptually than his 1949 New York Philharmonic version. Only with Walter's death in 1962, and Klemperer's in 1973, the age of the epicEroica was largely over. The blueprint remained, merely those who embraced information technology – conductors such as Sergiu Celibidache, Sir Georg Solti, Daniel Barenboim, and Sir Colin Davis in his 1991 Dresden version – could no longer fill the space or sustain the tension. An exception was Carlo Maria Giulini, whose 1978 Los Angeles recording has a touch more impetus than the strangely asleep reading that fellow countryman Victor De Sabata recorded in London in 1947. There are no divided strings and Giulini's conducting of the finale hangs burn, only his business relationship of theMarcia funebre is a powerful essay in stricken grandeur and adulterate hope.

FALLOW YEARS

The years between 1960 and the arrival of menstruation functioning in the 1980s were strangely dormant. It was as if, in the words of Oscar Wilde'due south Lady Bracknell, 'anybody has practically said whatsoever they had to say, which, in about cases, was probably not much'. Eugen Jochum recorded theEroica four times between 1937 and 1976; all are different, yet all sound much the same. A succession of conductors – André Cluytens, Rudolf Kempe, Ferenc Fricsay, Karl Böhm and Rafael Kubelík – were invited to tape the work with the Berlin Philharmonic on the assumption that their own and the orchestra'southward experience would exercise the flim-flam. It rarely did.

The ascendant figure during these years was Herbert von Karajan. His earliest survivingEroica is a 1944 studio recording with the Prussian Land Orchestra, Berlin. Compared with his 1952 Philharmonia account, the earlier reading is seriously undeveloped, though it offers a theatrically powerful business relationship of theMarcia funebre. Karajan's essentially lyric-dramatic view of the symphony – Cardus'south 'strongly shaped example of musical fine art' – finally came of age in his 1962 Berlin recording, though it is arguable that his finestEroica was his concluding, fabricated in Berlin in 1984. There is an added urgency here that comes at no cost to the reading'due south Walter-similar humanity and breadth of phrase.

For the residuum, it was the smaller stalls which offered the fresher produce. Enigma gave the states James Loughran's finely schooled reading with the Hallé (2/77 – nla) and Symphonica let Wyn Morris loose on the work (12/77 – also nla). A lifelong Furtwängler admirer, Morris conducts theEroica much as Richard Burton would have declaimed it, if such a matter were possible.

THE Menses REVOLUTION

Every bit the digital historic period dawned, only Günter Wand, among traditionalist interpreters, gave much satisfaction, serving up his Weingartner-style skillful lean beef. There was immense relief, therefore, when the early music movement stepped up to the plate.

Non everything worked. The all-time period-instrument accounts of theEroica are closely edited studio recordings. Alive performances, such as Frans Brüggen'south big-scale, combative account with the Orchestra of the 18th Century, were generally too poorly tuned and executed to comport repetition. A classic instance of the record-maker'southward arts and crafts is Christopher Hogwood's recording with the Academy of Aboriginal Music, an exquisitely clean-cut thing whose only omission is a sense of the sheer scale and danger of the slice. John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique evangelize those qualities in spades with pacey, virtuoso playing. Alas, the speed of commitment in the outer movements makes it virtually impossible to hear the music. Past the stopwatch Roger Norrington is merely as quick, simply his relish for the music's inner content – salient particular turning upward like sixpences in an old-fashioned Christmas pudding – is thrilling to hear, as is the tiptop playing of the London Classical Players.

If performances such every bit these helped throw new light on the symphony, most disaster followed every bit the 'flow' artful took hold, convincing over-aggressive chamber ensembles, and conductors bent on forcing modern symphony orchestras into the straitjacket of a 'period' style, that by adopting the menstruum formula they, too, might come up upwards with comparable insights into this titanic work.

One particularly damaging slice of pseudo-historical hokum was the merits that theEroica could or should exist played with an orchestra, as Richard Hickox put it, 'of the size Beethoven expected when he wrote it' – as if theEroica were conceived to accommodate a particular space or style. (In Beethoven's Vienna, the urban center's differing locations adamant an orchestra's size and, indeed, the speeds at which it might play.) In order to motility Michelangelo'sDavid to its appointed resting place, the Florentines had to knock down the walls of the Opera del Duomo where it was sculpted; to release Beethoven's Promethean utterance from its bondage, new orchestral strategies – new ways of articulating and pacing the music – had to be devised.

The finest 'bedroom'Eroica is Nikolaus Harnoncourt's, though the Sleeping accommodation Orchestra of Europe was no ordinary chamber orchestra. In size and character, this hand-picked 50-strong ensemble predicts the slimmed-down Berlin Philharmonic which COE Artistic Managing director Claudio Abbado would deploy in his ain memorable 2001 RomeEroica. Harnoncourt'southward is a mainstream modern-instrument performance, buoyed by its ain vitality and informed by the vision of a musician whose listen was steeped in the old ways of doing things. As such, it is light years away from the legion of overquick and punitively wham-bam chamber-orchestra versions of Sir Charles Mackerras, Thomas Dausgaard and others.

THE SYMPHONY IN A NEW CENTURY

Nowadays, speed appears to be de rigueur, yet as Channan Willner noted in an commodity in the Musical Times in February 1990, momentum in the German language tradition has less to do with speed, more to do with the pacing and shaping of a symphony's dramatic and rhetorical pattern. Ane of the fastest recent performances comes from Riccardo Chailly and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. The start movement, in which Chailly manages to combine high-octane bulldoze with an appropriate caste of expressivity, is atour de force. Simply speed is addictive, and information technology is this which ruins the later stages of theMarcia funebre and the finale, where there is barely a hint of joy or spiritual uplift.

Precipitate accounts of theMarcia funebre, once the accelerations begin at the oboe-ledmaggiore, are nothing new. (There is a peculiarly alarming example from the 91-year-quondam Leopold Stokowski.) Only information technology is odd to find conductors such equally Simon Rattle and the normally judicious Mariss Jansons falling foul of this, as Beethoven'southward dubiously fast metronome marker (dated 1817) is pursued and even overtaken. That said, there is a properly Beethovenian feel to the Jansons and to Rattle'south Vienna and Berlin accounts, which is non the case with the speedy and over-refined – almost Mendelssohnian – readings of conductors such as Paavo Järvi and Osmo Vänskä.

The recording which draws together the more than pertinent strands of latter-twenty-four hour period thinking about theEroica, and does so with a refinement of musical execution which protests lilliputian simply says much, is Claudio Abbado's live performance in Rome in 2001.

THE EROICA ON Film

The DVD of Abbado's RomeEroica is one of just two that merit mention. The beginning is a 1971 bespoke film directed by one of the founding fathers of the modern music video, Hugo Niebeling, with Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic. Niebeling seats the players in three steeply raked inverted triangles, looking a little similar ascending files of seats in an ancient Greek theatre with the conductor placed on the circularorkh¯estra below. There are some striking visual effects at key moments in this thrillingly articulated functioning, though there would have been more had Karajan not re-edited the film. In 2009, Niebeling released the original director's cut.

The DVD of Claudio Abbado's Rome performance is a model of its kind, with splendidly pertinent video direction past Bob Coles. The conductor-cam choice in particular provides us with a fascinating audible-visual experience, sharpening our sense of the reading itself while at the same fourth dimension providing unique insights into the mechanisms through which this astonishing artwork functions.

Peak Selection

VPO / Furtwängler (Orfeo)

No conductor articulates the drama of the Eroica – human and historical, individual and universal – more powerfully or eloquently than Furtwängler. Of his eleven extant recordings, it is this 1944 Vienna account, closely followed by the 1950 Berlin version, which virtually merits pride of place.

Menstruum-Instrument CHOICE

LCP / Norrington (Erato)

With the London Classical Players, the finest period-instrument ensemble of its day, playing under the management of the most insightful and theatrically aware 'menstruation' Beethovenian of the time, this gives u.s. a sense of what, in an ideal world, an early Eroica might take sounded like.

DVD CHOICE

BPO / Abbado (Euro Arts)

Filmed in Rome in 2001 with the 67-year-old Claudio Abbado directing a youthful-looking 'touring' Berlin Philharmonic, this DVD offers fascinating insights into how a front-rank conductor and informed interpreter of the Eroica articulates and manages the symphony alive in functioning.

STEREO Selection

VPO / Monteux (Decca)

With land-of-the art stereophonic sound doing total justice to Monteux's classically correct orchestral layouts, and with the Vienna Philharmonic in vintage form, this is a thrillingly 'complete' business relationship. Large-scale nonetheless vital, it'south what Austro-Germans call werktreu, true to the original.

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

Appointment / Artists / Record visitor (review date)

1926 Queen's Hall Orch / Wood / Beulah 2PD3 (4/27R)

1936 VPO / Weingartner / Naxos 8 110956 (eleven/36R)

1939 NBC And then / Toscanini / Music & Arts CD1275 (12/41R)

1944 VPO / Furtwängler / Orfeo C834 118Y (7/13R)

1944 Prussian St Orch / Karajan / Koch Schwann 315092 – nla

1950 BPO / Furtwängler / Audite AUDITE21 403 (ix/09)

1950 Concertgebouw Orch / E Kleiber / Decca 482 3952 (4/51R)

1951 BPO / Van Kempen / Decca Eloquence ELQ482 0270 (12/54R)

1951-52 RPO / Beecham / Sony SMK89887 – nla; Mastercorp Pty Ltd (one/54R)

1952 Philharmonia / Karajan / Warner 2564 63373-v (7/53R)

1957 Südwestfunk Orch / Horenstein / Vox 7807 – nla; BNF Collection (iv/60R)

1957 VPO / Monteux / Decca Eloquence ELQ480 8895 (11/63R)

1957 Cleveland Orch / Szell / Sony 88883 73715-2 (two/58R)

1958 Columbia SO / Walter / Sony 88875 12391-2 (3/61R)

1959 Philharmonia / Klemperer / EMI 404275-ii (3/62R)

1962 BPO / Karajan / DG 463 088-2GB5 (2/63R)

1964 NYPO / Bernstein / Sony 88883 71833-2 (10/66R)

1967 BBC SO / Barbirolli / Barbirolli Order SJB1040 (3/68R)

1971 BPO / Karajan / DG/Unitel 073 4107GH3 (5/06)

1978 Los Angeles PO / Giulini / DG 447 444-2GOR (five/79R, 8/96)

1984 BPO / Karajan / DG 439 002-2GHS (half-dozen/86R)

1985 NDR SO / Wand / RCA 88697 71144-2 (iii/86R)

1986 University of Ancient Music / Hogwood / Decca 452 551-2OC5 (11/86R)

1987 Orch of the 18th Century / Brüggen / Decca 478 7436DC7 (eleven/88R)

1987 London Classical Players / Norrington / Erato 083423-ii (4/89R)

1990 COE / Harnoncourt / Teldec 2564 63779-2 (11/91R)

1993 Orch Révolutionnaire et Romantique / Gardiner / Archiv 477 8643AB5 (eleven/94R)

2001 BPO / Abbado / DG 471 488-2GH (11/08R)

2001 BPO / Abbado / EuroArts 205 1138 (5/09)

2002 VPO / Rattle / EMI 915624-2 (iv/03)

2008 Leipzig Gewandhaus Orch / Chailly / Decca 478 3494DH (A/11R)

2012 Bavarian RSO / Jansons / BR-Klassik 900119 (12/13)

2015 BPO / Rattle / BPO BPHR160091 (6/16)

camaraporninexpent.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.gramophone.co.uk/features/article/a-guide-to-the-best-recordings-of-beethoven-s-symphony-no-3-eroica

0 Response to "Beethoven 3 5 7 1958 Solti Vienna Review"

Post a Comment